McEuen's metamorphosis

Tom Hasslinger | Hagadone News Network | UPDATED 15 years, 2 months AGO

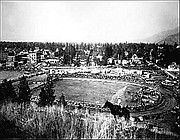

COEUR d'ALENE - Kids haven't always played ball at McEuen Field.

Where diamonds now lie dormant under winter snow, lumber once was milled.

The property has been home to horse racing, overflow barracks from Farragut Naval Base at Bayview, high school basketball games - and it also has served less ceremoniously as a dump.

Its century-old history begins with a lumber mill, one that sat where the city boat launch and Third Street parking lot is today, using the shores of Lake Coeur d'Alene to haul in logs and shipping the cut cargo on the railroad running through downtown.

When the mill closed in 1929 the park sat vacant. That was the same year the city of Coeur d'Alene began acquiring land around McEuen Field, then called Mullan Park.

And to fill in the ruined soil in the 1930s after the mill was gone, anything went.

"They were dumping anything they could find to fill the hole," said Larry Strobel, Museum of North Idaho board member and author of "When the Mill Whistle Blew," the book that chronicles Coeur d'Alene's history from 1888 to 1955. "You know, the Environmental Protection Agency wasn't around then."

Rip up the marina parking lot now and one might come across at least one old car, Strobel said. He remembers one family friend donating a worn-out vehicle to the hole-filling cause.

"Things were very different," he said.

Since then, the park has served as a horse racing track while home of the Kootenai County Fair. It housed overflow barracks for Farragut soldiers during World War II.

Every piece of property that comprises the public-owned 135 acres of McEuen Field and Tubbs Hill today was purchased by the city over eight separate sales between 1929 and 1980.

Nothing was ever donated.

Mae McEuen did not donate land for the American Legion baseball field, a misconception Parks Director Doug Eastwood said he hears often.

Mae McEuen, a grocery store owner who donated generously to youth sports, was the head of the first parks and recreation commission formed around 1955. The park was named after her on June 12, 1965, the year the American Legion baseball field was built.

Looking back, 1900 to 1997

Opening in 1900, the Coeur d'Alene Lumber Company couldn't survive the Wall Street crash of 1929. The city purchased its footprint, from Front Avenue to the water, for around $19,000, a deal Strobel's book calls "bargain-basement."

After filling in the soil during the 1930s, the lake lost a bay. But the park became home of the Kootenai County Fairgrounds in the 1930s and 1940s, with a horse racing track.

During the early 1940s it became a temporary barracks for soldiers from Farragut.

"Rows and rows and rows of them," Eastwood said of the wooden buildings that sprang up to house the overflow of young men waiting to go to war.

Strobel remembers soldiers milling about the nearby downtown on weekends, dressed in uniform with girls by their sides. After the war, the buildings deteriorated to cheap living, or "slums," as the author calls them.

"The workmanship wasn't very good, and they quickly fell apart," Strobel said. "That was our waterfront."

Later, Coeur d'Alene even used the officers' quarters for its parks and recreation department until 2002.

But by 1952, talk of replacing the buildings for public recreation was under way.

In 1954, the fair moved to the vacated airport at Weeks Field, and the current boat and parking lot were built in that decade too. By 1958, that's where crowds gathered for the Diamond Cup Unlimited Hydroplane Races.

But it was Mae McEuen who led the charge turning the deserted land into a recreational spot of green space. After the hardball field came in, the softball fields followed in the 1970s.

"I think rather than saying she was a baseball lover, she was more interested in the youth," Strobel said of Mae McEuen, whose grocery story on East Sherman Avenue he remembers frequenting. "She was very instrumental in making sure the youth in this town had something to do."

Change in the air, 1997 to present

In January of 1997 Resort and Press owner Duane Hagadone offered to pay for a $5.7 million project that would have brought a new public library and memorial gardens to McEuen Field.

The 1997 plan included removing the ball fields and eventually removing the boat launch, according to a Feb. 1, 1997, article in The Press. Around 300 people showed up for a public meeting later that month, and many people spoke against the idea, another Press article states.

"It just died," 40-year Councilman Ron Edinger remembers, adding that the gardens didn't offer enough recreational opportunities. "There were some issues that concerned the public and it just kind of lost momentum."

But in 1997, city officials knew something had to be done with the field at some point.

The city hired a consulting firm, Hyett-Palma, to outline an economic revitalization plan for its downtown, and the study recognized McEuen Field as a site that could be a destination place and boon to the economy. That same year, the city created its urban renewal agency, Lake City Development Corp.

The downtown park was intentionally included in urban renewal's Lake District boundary for the reason that the agency, once tax monies were collected, would help fund a reconstruction project someday.

"We knew we needed to create a higher and better use of this waterfront corridor," Eastwood said. "But if we were to do that, nobody came to any conclusions."

In 1998, LCDC contracted for a follow-up study, the Walker/Macy Downtown Public Places Master Plan. Unlike the one before it, this study focused more specifically on how to enhance McEuen Field.

The plan pitched many ideas - including removing the boat launch - in its $14.4 million in long-range enhancements. The aim was to get vehicles off the property with the city's best views.

But just as before, opponents voiced concern.

In response to public comment taken on Jan. 7, 2000, Walker-Macy came back and said the boat launch shouldn't be closed until a viable, year-round alternative could be found. A proposed launch site on Blackwell Island was not a sufficient replacement, the consultant said.

Taking this study, the city then formed the Committee of Nine in 2000, a team of citizens who took three years of information and drew a conceptual plan of the park.

Before doing so, the group formed a set of seven values it would follow.

Those values outline creating a public space that links to the downtown and waterfront. But to move anything, the committee promised No. 5: "Ensure the replacement of any displaced facilities with equal or better facilities." The conceptual draft the committee penned over two years did not include the baseball field in its plans.

It was adopted by the City Council in 2002 as the official conceptual plan, but with the understanding there wasn't money in city coffers to think about breaking ground soon.

"Nothing says we can't change it in five, 10 or 15 years," a Press article quotes Councilwoman Dixie Reid as saying at the plan's unveiling. "This is something that is always in motion; it's a beginning point."

McEuen could change in 2011

At 6 p.m. this Thursday, the latest McEuen conceptual plan will be introduced to the public at North Idaho College.

It calls for a complete, yet-to-be-priced overhaul that includes a skating rink, a sledding hill on Tubbs Hill, a water fountain, pavilion, concert stage, and tennis, pickle and bocce ball courts.

Developed by a team of local architects, it cost around $125,000.

The Walker-Macy and Hyett Palma studies cost the city around $218,000, and it spent $11,600 for the conceptual design the Committee of Nine had drawn from those.

The $354,600 in plans and studies that have now been spent in the last 12 years is more than the $300,000 the city spent acquiring the park and Tubbs Hill from 1929 and 1980. That footprint is closer to $200 million now.

But this time around, funding to break ground could be in place.

LCDC is ready to act. Last year, it approached the city and asked the council to put McEuen high on its radar as the urban renewal boundary is set to expire in 2021. It then set aside $500,000 in fiscal year 2011 to get the project going.

But just as before, some still question the changes.

"It's sad to see it go," said Conrad Chisholm, who has been involved in the American Legion program since the mid-1960s.

The ball field isn't a part of the new design and a replacement facility hasn't been tracked down yet. The city thought it had a spot for a new field years ago, but the Kroc Community Center was put there. While at McEuen Field, pro baseball players Ryne Sandberg, Jason Bay and Bobby Jenks played there at one point.

"I can understand some of the thinking," Chisholm said. "But they're not realizing how many people use that field."

Activist Steve Bell plans to circulate a petition opposing the boat launch removal, just as he had done a decade ago when the idea was introduced. He said the replacement launches don't compensate for the loss since one is closed half of the year.

"This isn't a rich man's lake," he said of the public not being able to drop their boats at Third Street. "Close the launch and that's what it becomes."

ARTICLES BY TOM HASSLINGER

Hydro races return to area

COEUR d’ALENE — Lake Coeur d’Alene is shining like a diamond this weekend.

Live After 5 to debut in downtown Cd'A

Free summer concert venue to entertain on Wednesday evenings

COEUR d'ALENE - Tyler Davis is a musician himself, but he says he won't take the stage.

Pushing aside the anger

Darleen Haff was sixth woman admitted to UGM program in Cd'A

COEUR d'ALENE - Darleen Haff first kicked her drug habit by replacing cocaine with alcohol.