Coast Guard honors rescue pilot

The Western News | UPDATED 10 years, 2 months AGO

NEW LONDON, Conn. — A World War II pilot whose lost plane has become the target of a stepped-up U.S. recovery effort in Greenland was honored Friday by the Coast Guard Academy, which commended him for heroism shown during daring rescue missions on the frozen tundra before the one that killed him in 1942.

The pilot, Lt. John Pritchard, was inducted into the Hall of Heroes at the academy in New London, where he graduated in 1938.

“John was a very friendly, caring person,” said his sister, 91-year-old Nancy Pritchard Morgan, who received an ovation from cadets in dress blue uniforms at the ceremony. “He loved his family, he loved the Coast Guard, he loved flying, he loved life. His actions on the Greenland ice cap read like his whole life.”

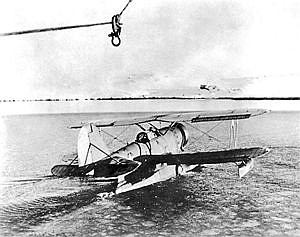

Pritchard was trying to save a man left stranded on the tundra by the crash of a B-17 when his own single-engine Grumman Duck plane went down in whiteout conditions, killing a total of three U.S. service members.

Recently discovered evidence of the wreckage, which is now entombed in a glacier, has launched several recovery missions in recent years, including a mission to Greenland this summer by the Joint Personnel POW/MIA Accounting Command. The plane may hold the remains of the Coast Guard’s last two MIA service members, Pritchard and his radioman, Petty Officer 1st Class Benjamin Bottoms.

Pritchard, a California native, was assigned to a cutter conducting war-time patrols in the waters off Greenland when the U.S. Army Air Forces B-17 crashed on the ice cap during a search mission. The crew survived but was marooned on the tundra. Pritchard launched his amphibious plane from the cutter’s deck, landed on the ice cap and returned with two of the injured survivors. It was the first successful landing on the ice cap, the Coast Guard said.

The next day, Nov. 29, 1942, Pritchard and Bottoms volunteered to return. They picked up another survivor but crashed after takeoff. Pritchard was 28.

The honors awarded Friday were in recognition of another dangerous rescue mission, led by Pritchard only six days before his fatal crash, in which he traveled by land to save three members of the Royal Canadian Air Force who had been stranded on the ice for nearly two weeks. His name was added to a wall of honor inside the cadets’ residence hall.

The new push to recover Pritchard’s plane began in 2010 with the first in a series of expeditions by a private company, North South Polar, and the Coast Guard to investigate what on radar appeared to be the plane’s wreckage. Photographs taken through holes bored into the ice appeared to show plane wreckage deep in the ice, but when a U.S. military team returned last summer, there was nothing to be seen in the same spot, according to Cmdr. Brian Glander, the chief of the Office of Aviation Forces at Coast Guard headquarters.

Pritchard’s sister said the outcome was frustrating.

“It was exciting. It was wonderful, and then frustrating and devastating. They had almost found it,” she said, “then went back and couldn’t even find it.”

Glander said the wreckage may have shifted in the ice, but there was no time for an expanded search in the short period of good weather. He said nobody is giving up on the mission.

“It’s safe to say the case is not closed,” Glander said.