Civilian Conservation Corps — The Tree Army

MARYLYN CORK Contributing Writer | Bonner County Daily Bee | UPDATED 3 years, 8 months AGO

This story is adapted and shortened from a series by Jeff Peterson that ran in consecutive weeks in the Priest River Times in 1980.

The Civilian Conservation Corps, more familiarly known as the “CCCs” and also as the “Tree Army,” was a depression-era brainstorm of Franklyn D. Roosevelt and his advisors. FDR created the agency in 1933 as part of his New Deal program.

About four million unemployed young people, mostly male, were put to work by the program that was initiated in 1931.The purpose was to employ young people in the revitalization of natural resources while instilling a strong work ethic in them and giving them job training for the future. More than 4,000 CCC camps were established. Camps were in every one of the then 48 states, plus four territories: Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands.

Military officers ran the camps and Forest Service personnel provided much of the expertise, especially in the local area. Enrollees were generally paid $30 a week. Twenty-five dollars of that amount was sent home to help their families.

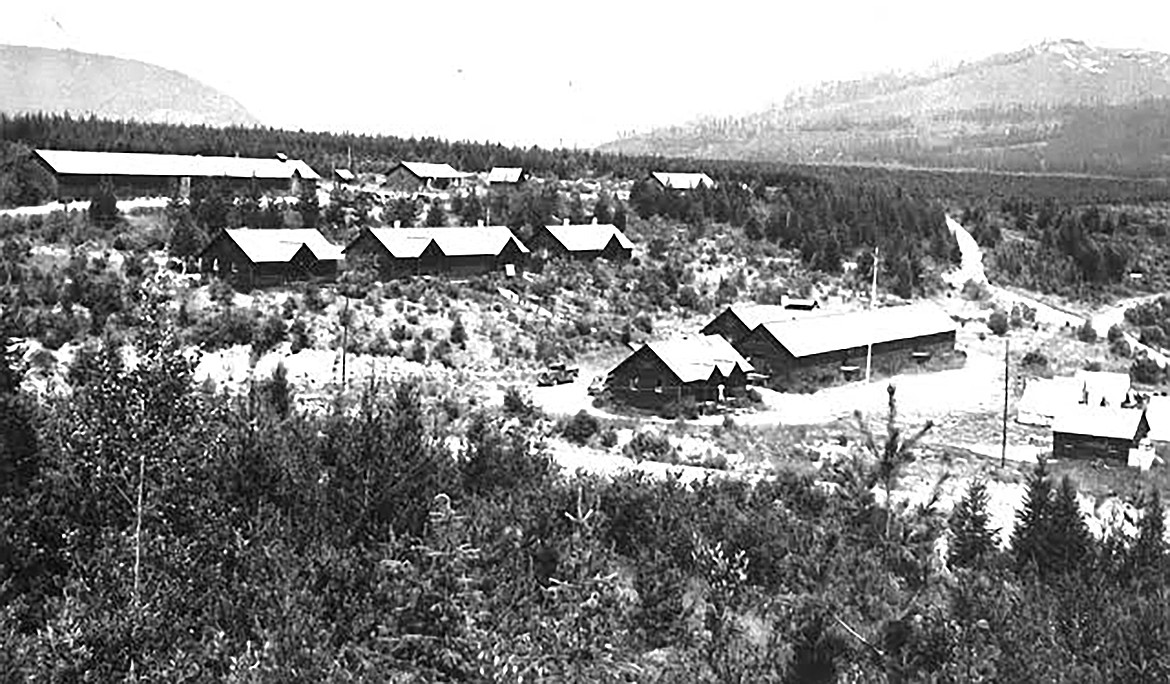

The average camp was a city unto itself. Springing up in a forest clearing, buildings included a kitchen, mess hall, school, infirmary, recreation center, enrollee barracks and officer quarters.

As one recruit, Tom Kinner, from Ohio, said many years later, “We got three square meals a day, medical and dental paid for, plenty of clothing and money to spend. The CCC’s were the only thing left for most of these fellows from back east. There was no work back there. In Ohio, all we were doing was getting into trouble.

“I liked it from the first day I came out here. It was the best thing that ever happened to me.”

Reveille was typically at 6 a.m. with breakfast at 6:30, then came sick call and policing of the site. By 7:15 a.m., trucks were loaded with men and tools for the drive to the day’s worksite. A 30-minute lunch break came at noon, and work was over for the day at 4 p.m. A Retreat ceremony was held back at camp at 5 p.m., with lowering of the flag and announcements. Dinner followed, after which recruits were free to read, write letters, attend classes, play softball, visit with friends or participate in other activities, such as horseshoes, checkers, chess and bridge tournaments, track meets, etc.

CCC boys at the Big Creek and East River camps floated log rafts into town, a practice the Times’ editor opined was foolhardy and that posed a drowning risk.

The boys were free on weekends to visit neighboring towns. At first, it was tough to fit in, and there was a lot of give and take from both sides when it came to pranks. Priest River’s young men took the CCC boys on snipe hunts. The local dances were well attended.

The Priest Lake area’s first three camps of 300 boys broke ground by June 22, 1933. They were Big Creek, Indian Creek and Kalispell Creek, at the old Diamond Match landing. The boys were soon set to work cleaning up old forest fire burns, building trails, and controlling and trying to eliminate blister rust. They also began road building work from the Outlet to Luby Bay.

By mid-summer of 1933 the CCCs had also built a road to the lookout on Looking Glass Mountain (now Gisborne) repaired and painted buildings at the Experiment Station, and thinned overstocked white pine.

In something like 10 weeks in the woods, they had finished Johnny Long Mountain Trail, the Blue Creek Trail, the Fisher Cabin Trail and others, and had cleared two miles of right-of-way for the East River road. For their efforts, they earned a weekend trip to Spokane.

They were shipped to winter camps or sent home in early October.

In 1934, more camps were established as the blister rust work sprang into high gear. Six new camps in the Priest Lake area were Blowdown No. 1 and No. 2 in the West Branch country, Gleason, Boswell, Four Corners and Beaver Dam.

Friendly relations had progressed to the point that Priest River welcomed the boys back with a big celebration on May 10. One thousand boys came into town. They were treated to a free show at the Rex Theater and dancing, among other activities. Camp foremen and officers met with town business men at the Odd Fellows Hall.

However, all was not always roses. What has been termed “the lowest point in the history of the CCC at Priest Lake” occurred in early July. After putting out a barn fire at the Anselmo ranch, which earned big points from the locals, a new contingent of men with eight blacks arrived at High Bridge camp. Almost immediately there was trouble. A black boy attacked one of the whites with a knife. Another black threw an axe at a white boy. (Who knows what provocation precluded it all.)

The Priest River Times reported, “That evening when the negroes had retired, they were all tied up and thrown into an awaiting truck and taken part way to Spokane where they were dumped out and told to be on their way. Nothing was known of the incident at the camp until the next morning when roll call was taken.” That ended the lake’s “race war.”

Much of the business that summer was fighting fire, locally, and near Missoula, Mont. A later fire sent others to an “uncontrollable” blaze in the Selway. Two of the fire fighters lost their lives and another was seriously injured, but it ended the bad fire season for that year.

By early September, Kalispell Bay, Rannels Creek and Four Corners camps were making preparations for housing CCC boys through the winter. Those camps were falling snags, work that could continue in the snow.

A falling snag hospitalized a boy at Four Corners Camp, and a strong wind killed a boy in late September at Kavanaugh (now spelled Cavanaugh) Bay in blowing a tree across four tents. Late that month Priest River’s marshal arrested three boys for being drunk and disorderly. They ripped up the local jail and got 60 days for their trouble.

After the CCCs began leaving the area in late October, Kalispell Bay was converted into a year-round facility. Veterans of World War 1, who made up a small force of CCC enrollees but who usually had their own camps, moved into Blow Down No. 2 at Rannells Creek, for the winter.