'Two Terrible Days:' The 1910 Fire

JORDAN THOMAS/Contributing Columnist | Shoshone News-Press | UPDATED 4 years, 4 months AGO

“One observer said the air felt electric, as though the whole world was ready to go up in spontaneous combustion.” 111 years ago, on Aug. 20, 1910, winds from the Palouse whipped through North Idaho and Montana. Hundreds of fires that had been burning throughout the summer were blown into one massive inferno that no one was prepared for. Ranger Elers Koch wrote, “In those two terrible days many fires swept thirty to fifty miles across mountain ranges and rivers.” Many communities were in danger, Forest Service Rangers and firefighters were trapped in the mountains, miles from any town, and women, children, and the sick from the hospitals were evacuated as quickly as possible on trains as flames bore down on Wallace.

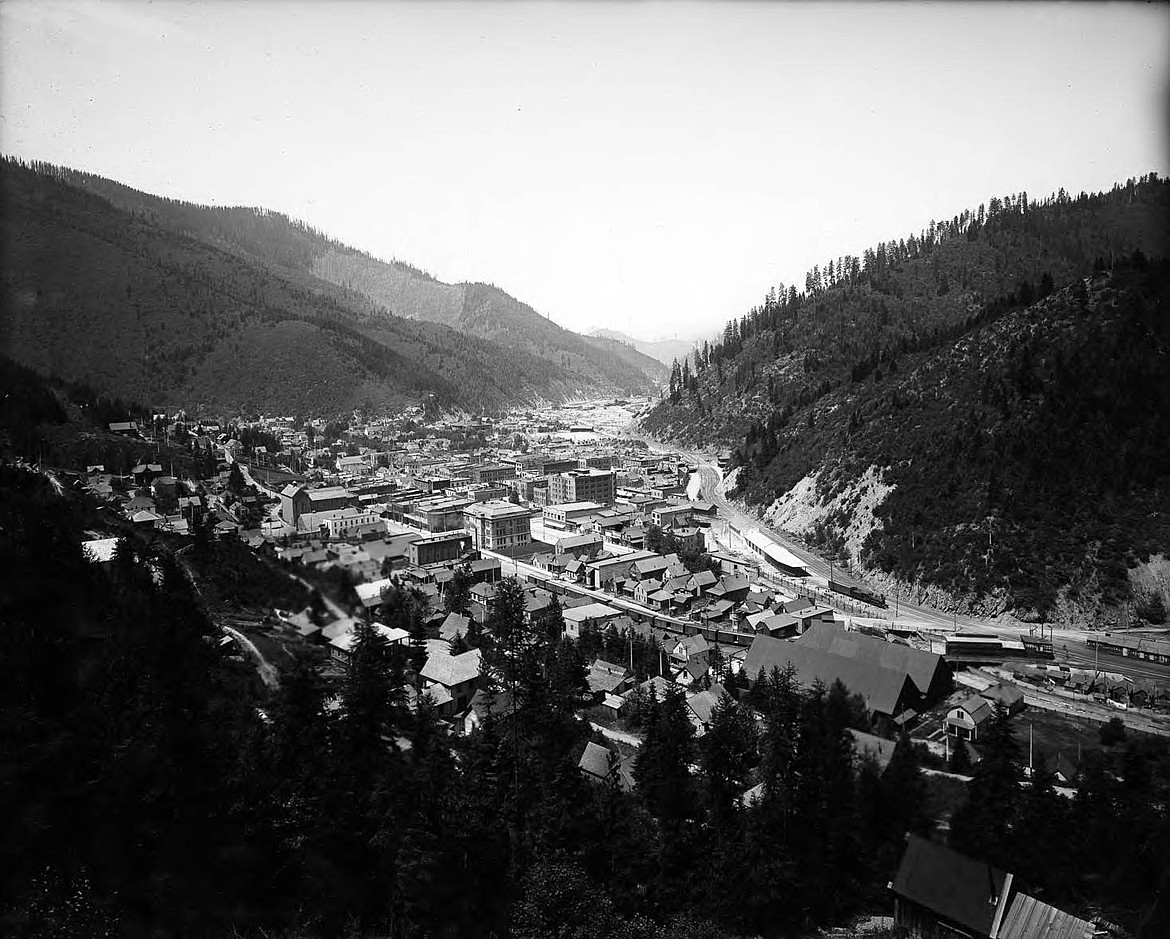

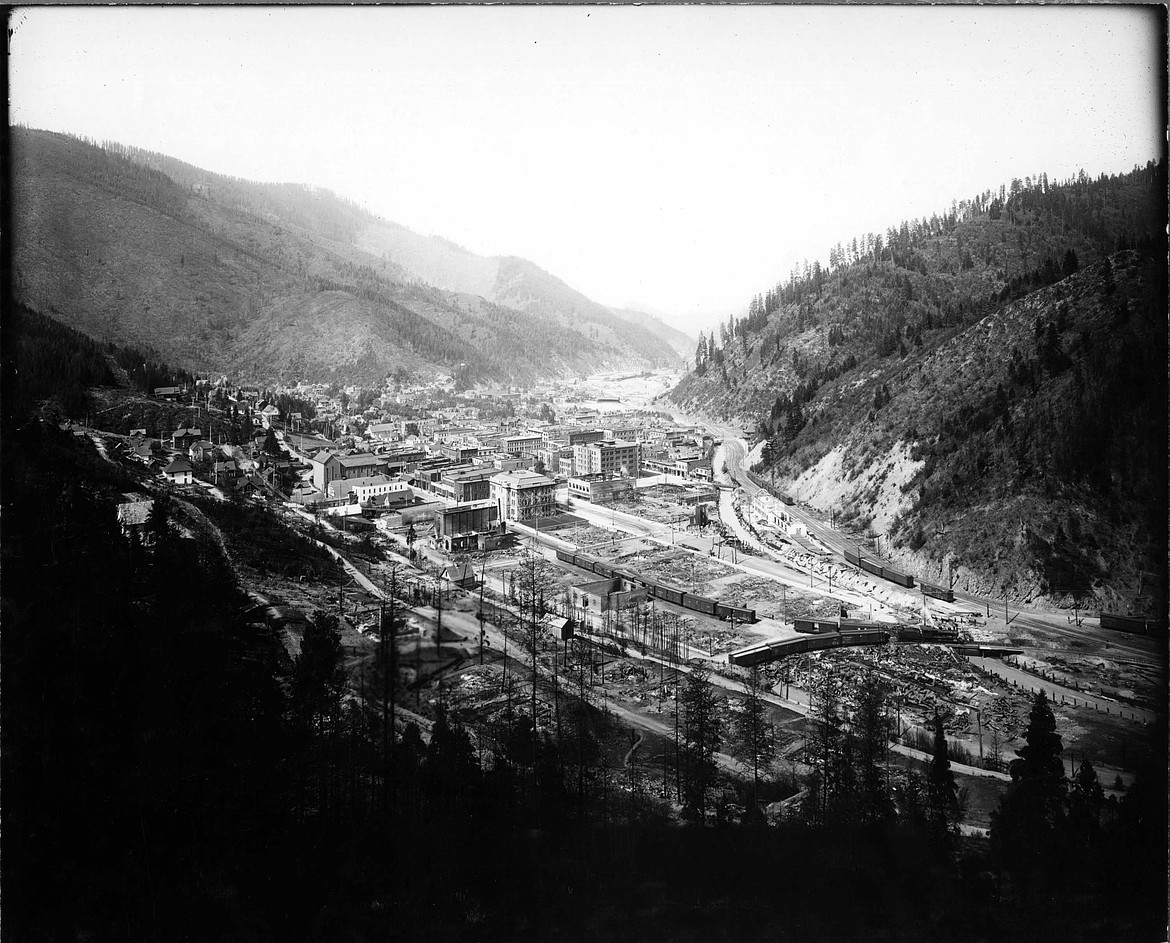

The people of Wallace had been worried about the number of fires burning nearby all summer, especially given that just 20 years earlier most of the town and hillsides had burned to the ground. On Aug. 14, after awnings in town had caught fire from fire brands from fires miles away, the local insurance companies found themselves swamped with business. They were selling fire insurance policies to everyone in town and continued to do so until about noon on the 20th when the wind began to blow.

When the winds picked up on Aug. 20, the greatest danger to Wallace was a fire raging down Placer Creek. A letter sent by the manager of the Bunker Hill Mine stated, “Saturday evening, about 8:00 o’clock, the fire burst over the hill back of Wallace and ignited the buildings closely adjacent to the O.R. & N. depot. Within a short time everything was burned east of 7th st., the street on which the Samuels hotel is situated.” As the fire came over the hillside women, children and the sick were loaded onto relief trains headed for Missoula and Spokane as those still in town did everything they could to save it. When the wooden building that housed the Press-Times caught fire, the flames caused gasoline stored there to explode. The surrounding structures caught fire and it blew out of control, driven by high winds.

Most of Wallace survived the fire due to backfiring, citizens working to wet yards and fight small fires that started, and finally, because the winds shifted and the fire burned back into itself.

One of the most well-known stories of the Big Burn is that of Ed Pulaski and his heroics. Pulaski was working as a Forest Service Ranger in 1910 and when the fires began he was in charge of a team of about 150 firefighters in the mountains above Wallace. When the danger of their situation became obvious he gathered around 40 of his men and started for Wallace, about 10 miles away. About half-way to Wallace, they found their route blocked by fire. Pulaski’s men began to panic but Pulaski knew the area well and assured his men he could still get them to safety.

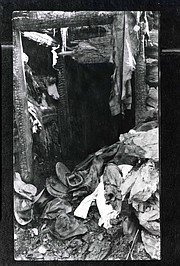

Pulaski knew of a mining tunnel nearby that he and his men could hide in and wait out the fires. Forty-two men and two horses made it to the mine tunnel just as the fires reached them. When the smoke began filling the tunnel and his men started to panic, Pulaski stood in the entrance with his pistol and threatened to shoot anyone who tried to leave. He knew exiting the tunnel would mean almost certain death. The timbers near the mouth of the tunnel caught fire and Pulaski stood as near to the mouth of the tunnel as he could and used his hat and a horse blanket to splash water from the bottom of the tunnel onto the timbers until he was badly burned and fell unconscious. After the fires had passed, one of Pulaski’s men was able to make it to Wallace and notify the Forestry Office to help the other men.

Only five of the men in the tunnel passed away from the smoke and lack of oxygen. The rest were taken back to Wallace and recovered rapidly. Had Pulaski not known the location of the tunnel and taken his men there, the death toll of the Big Burn would have been much higher.

In the end, the Big Burn incinerated nearly three million acres in just a few days. Around 1 a.m. on Aug. 22, 1910, the wind and the humidity changed and the fires slowed down. On the night of the 23rd, the much prayed for rain finally fell after a hot, dry summer. Snow fell at some of the higher elevations and brought the 1910 fire to an end.

Many of the fires continued burning, but at a much slower pace until a good and soaking rain finally fell in the beginning of September. Will Morris and his crew woke to rain on Sept. 4, 1910. Morris wrote, “First only a few (raindrops) fell, and then, increasing, it soon began to come down quite heavily. We lay there and enjoyed it. We were glad to get wet, for we knew our long fight was over.”

One third of Wallace had burned, towns such as Taft and Grand Forks had been completely destroyed, homes had been lost, prime timber country had burned, and 85 people had lost their lives in the Big Burn, majority of whom were firefighters on the frontlines.

In his 1942 history of the fire, Elers Koch wrote, “The tragic and disastrous culmination of that battle to save the forests shocked the nation into a realization of the necessity of a better system of fire control.” The Big Burn helped to shape Forest Service and firefighting policies that are still in place today. It changed the way America viewed wildfires.

Ed Pulaski also changed the way fires are fought by creating the Pulaski tool that is still used by wildland firefighters today. Pulaski continued working for the Forest Service after the fire, despite his injuries. He spent his free time inventing the Pulaski tool and tending the graves of those who died in the fire. He spent many years asking the government for the money to create a memorial to honor those who had died. Finally, in 1921 he was granted enough money to have their names etched in stone. In 1933, two years after he passed away, a final memorial was created in St. Maries. The memorials can still be visited today in St. Maries and Nine Mile Cemetery in Wallace.