How did we get here? Health misinformation flourishes

AUDREY DUTTON/Idaho Capital Sun | Coeur d'Alene Press | UPDATED 3 years AGO

Editor’s note: This is the second story in a three-part series this week on health misinformation, vaccine hesitancy and distrust in Idaho. The Idaho Capital Sun interviewed dozens of people, asking how the state ended up on a path to catastrophe — and what, if anything, can turn it around.

State legislators, public health officials, lawyers, health care workers and a media scholar all described one common theme: distrust, fueled by forces within Idaho and beyond.

The state was ablaze with the delta coronavirus variant in early August, when Connie visited her hometown in eastern Idaho. Connie — who asked we use only her first name due to concerns about blowback on her family — was fully vaccinated against COVID-19. Much of her family was not, including her octogenarian parents.

When she got to Rockland, a tiny farming town with fewer than 300 residents, there was a community picnic at a park. And not a mask in sight.

“For me, coming from California, I was just shocked,” Connie said in an interview this month. “And at this point, I started thinking to myself, ‘This is not good.’”

Connie spent her visit trying in vain to persuade her 80-year-old mother that COVID-19 vaccines were safe. By the end of the month, her mother was one of more than 4,000 Idahoans to die of COVID-19.

Public health officials have pleaded with Idahoans for a year to get vaccinated. But a flood of false and unsupported health claims have drowned out their pleas.

How did Idaho reach this point, where an 80-year-old woman refuses protection against a virus that has killed off 3% of Idahoans in her age group?

In dozens of Idaho Capital Sun interviews this year, experts in public health, the law, medicine and media literacy said the pandemic shone a light on the fabric of public trust in Idaho. What it exposed was the wear and tear of decades of health misinformation, deregulation and spotty oversight.

‘She was being terrorized’

As in Idaho’s other remote communities, the coronavirus arrived late in Rockland. The first real outbreak in all of Power County wasn’t until July 2020, according to public health case data.

Connie’s parents were, like many Idahoans, devout members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Senior leaders of the church took the COVID-19 vaccine in January, and the church publicized it. The week of Connie’s visit to Rockland, the church’s prophet and his counselors issued a statement urging Latter-day Saints to get vaccinated and to wear masks.

“We can win this war if everyone will follow the wise and thoughtful recommendations of medical experts and government leaders,” they wrote in the Aug. 12 message.

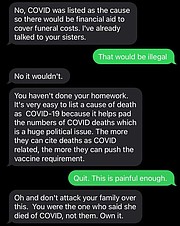

That resonated with Connie’s father. He went with her to a pharmacy for his first dose. But months of emails, forwarded memes, text messages and disinformation on television and social media had convinced Connie’s mom that COVID-19 vaccines were deadly, she said.

“It was just on her phone, 24/7, coming at her from people she trusted, community members. … And then she would see validation on Fox News,” Connie said. “She was being terrorized about the vaccine. Just terrorized.”

It wasn’t limited to Idaho. People around the U.S. and the globe consumed false information about COVID-19 and vaccines — be it disinformation spread deliberately, or accidental misinformation.

“Misinformation about health care topics is nothing new, but social media, the polarization of news sources, and the pace of scientific development on COVID-19 have all contributed to an environment that makes it easier than ever for ambiguous information, misinterpretation, and deliberate disinformation to spread,” the Kaiser Family Foundation wrote last month, after surveying about 1,500 adults.

Nearly 80% of adults said they’d heard at least one of the major myths surrounding COVID-19, and either believed the myths to be true or didn’t know if they were true or false, the survey found.

A survey commissioned this fall by the Frank Church Institute at Boise State University found that 83% of adults in the Rocky Mountain West — Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Utah and Wyoming — believed “misinformation” and “misrepresentation of facts” are threats to democracy.

Where they seemed to disagree, though, was on what constitutes misinformation. Republicans surveyed were more than twice as likely to say “there is a lot of misinformation spread on news media,” the institute’s report said. About 33% of those surveyed said they get their news from social media.

Health care in Idaho underwent a subtle transformation

Throughout the pandemic, health officials have urged Idahoans to seek information on COVID-19 from trusted sources.

The public’s most trusted sources of health information are doctors. People with less access to them turn to the internet first, according to national surveys before and during the pandemic.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently published a report showing that people were more likely to be vaccinated if their health care provider recommended it.

Idaho has a dire shortage of those trusted health advisers.

There are 1,034 Idahoans for every primary care doctor in the state, according to a Sun analysis of data from the Kaiser Family Foundation and census data. Idaho ranks 49th in the nation for primary care physicians per capita.

Idaho lawmakers tried in the past two decades to narrow that gap — from giving nurse practitioners the ability to work independently as primary care providers, to committing to help create more medical residencies and supporting Idaho’s first medical school.

Other changes, though, eroded trust in the medical community, according to Susie Keller, CEO of the Idaho Medical Association.

“I think our state in particular, because we have kind of held ourselves out as a low regulation state, I think nationally we are a target,” Keller said in a July interview. “So, when a group of health care professionals wants to expand their scope nationally, Idaho is among the states they target, because we have this reputation.”

For example, Keller said, in the last legislative session before COVID-19 reached Idaho, optometrists pushed for a bill giving them authority to perform laser surgeries — procedures done by ophthalmologists, who are medical doctors.

“There also in recent years has been a chilling effect on regulating acts of health care providers,” Keller said.

A U.S. Supreme Court case involving a dentistry board in North Carolina ended in a 2015 decision that, for some professional licensing boards, it is a potential antitrust violation to limit what other professions do.

The case “sent ripples throughout the country,” Keller said. “That has really tamped down any licensure boards that were going to be proactive about defending their scope. That really took that (movement) back several steps.”

Medical and osteopathic doctors “have seen a dissolution and redistribution of their scope of practice over the past 15 or more years, as well as the dilution of their clinical authority,” a 2018 Idaho Medical Association resolution said.

Idaho gives patients few avenues to hold doctors accountable for harm. But for other professions, there are “nascent to limited systems for the vetting of adverse outcomes or complications for … incidents with patients, clients or customers,” the resolution said.

For example, chiropractors in Idaho have a wide scope of practice. They can prescribe on a limited basis, hook up patients to IV drips, and act as primary care providers. Many Idaho chiropractors advertise treatments for autism, chronic fatigue or even clogged arteries.

They also treat fictional disorders, such as “rope worms.” Co-founded by a local chiropractor, Meridian company Microbe Formulas sells a package for $907 that includes a “gut and immune support” line of products. In product reviews, customers share photographs of “rope worms” they believe to be parasites.

“I have large and small critters exiting daily,” one customer wrote.

Released from the body in long, stringy bowel movements, the worms are actually fecal matter and mucus. A substance in some gut-cleanse products thickens into a snake-like mold of the intestines.

“Rope worm, or Funis vermis, is not yet a scientifically ‘confirmed’ parasite,” the Microbe Formulas website says. (Funis vermis isn’t an official scientific name for the excretions; it’s “rope worm” in Latin.)

Marketing representatives told the Sun they were unable to comment, and that Microbe Formulas’ owners were unavailable.

Proving ground for ‘health freedom’

As officials toured the state in 2019 to hear public comment on regulations, the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare was bombarded with comments from people who opposed vaccine rules.

More than two dozen people testified that they moved to Idaho “because of the state’s limited regulation — specifically, the ease of getting a vaccine exemption for schoolchildren,” the Idaho Statesman reported in February 2020.

“Several people who testified at hearings or via email described themselves as a ‘refugee’ of their former state. They urged lawmakers and the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare not to change Idaho’s permissive rules,” the Statesman article said. “Neighboring states like California and Washington have tightened the rules for vaccine exemptions in response to outbreaks of diseases like the measles.”

Several people the Sun interviewed from the Idaho Legislature, health care community and academia said Idaho has cultivated that reputation — and is attracting newcomers who believe they will find a deregulated nirvana.

Gov. Brad Little announced in December 2019, just before the pandemic, that Idaho had become the least regulated state in the U.S.

Regulatory reform was among Little’s projects when he took office in January 2019. Some of Idaho’s rules were redundant, antiquated or useless. Within months, state officials had eliminated 40% of Idaho’s regulations.

Little told the Idaho Statesman that the White House, federal and state government officials “came up to us and said, ‘What is happening in Idaho? We are hearing about all the rules.’ And I am more than a little proud about that,” according to Statesman reporting from July 2019.

Long before that, though, Idaho lawmakers set some of the most lax vaccination rules in the U.S. Parents in Idaho can send children to public school without immunizations, for any reason.

The Idaho Legislature this year changed the law. It now requires schools to explain, “in any communication to parents and guardians regarding immunization,” that they can exempt their child from vaccination for any reason.

During the pandemic, legislators also changed laws to pull state funding from public health departments, and to give elected politicians veto power over public health mandates.

‘I couldn’t undo the damage'

Connie left Rockland on a Sunday in mid-August. She begged her mother and father not to attend church that day. She figured they would, so she gave them N95 masks to wear.

They went to church and didn’t keep the masks on, she told the Sun.

A week later, her mother and father tested positive for COVID-19.

Her father recovered quickly, even though he was exposed to the virus just a few days after his first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Connie’s mother developed pneumonia. Her oxygen levels plummeted, and she was admitted to the hospital.

Her condition worsened. Doctors told her she needed a ventilator.

But misinformation got in the way. Connie’s mother refused.

She had been exposed to the myth that ventilators kill COVID-19 patients — a misinterpretation of the high mortality rates among patients who are sick enough with COVID-19 to require ventilators.

Many people do not survive after intubation. Patients who need to be intubated and placed on a ventilator are already gravely ill. Their doctors have determined they need an external lung to breathe for them, in order to have a chance of leaving the hospital alive.

Connie’s mother died on Aug. 30, one of the 11 Idahoans with COVID-19 to die that day.