Algae Alive! Innovative science project engages students during pandemic

HILARY MATHESON | Hagadone News Network | UPDATED 4 years, 7 months AGO

As schools shut down and students were quarantined during the pandemic, educators such as Glacier High School science teacher David Lillard sought ways to give students a hands-on experience whether they were at school or at home.

In Lillard’s case it was a lab he came up with called Algae Alive!, drawing inspiration from an experiment he saw on display at a Seattle science conference he attended with colleagues prior to the pandemic. Algae Alive! ties into a unit on ecology and lets students design an experiment using algae and brine shrimp by coming up with their own questions, hypotheses and independent variables.

Through a Kalispell Education Foundation $1,098 grant, he was able to purchase supplies and equipment that would be easily accessible to students on campus or at home. He has also reached out to other teachers about adapting the project to the elementary and middle-school level.

“I’m always looking for ways that we can have living things in the lab that we can experiment with,” Lillard said. “It’s hard to find living models that, you know, are cheap and can be used effectively in the classroom without a lot of equipment, and I just thought it was a cool idea. It’s actually its own little ecosystem.”

FORTUNATELY, WHILE the lab was being conducted in his Advanced Placement (AP) biology class last month, all the students were attending school on campus.

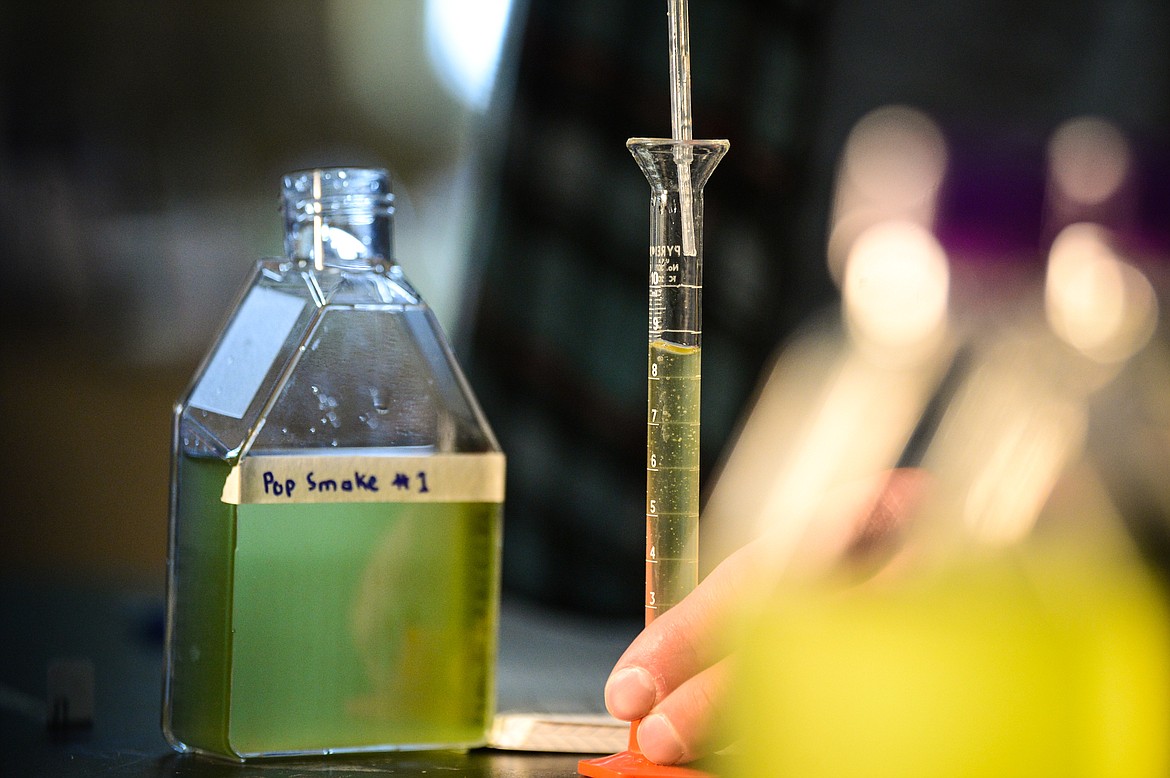

On April 21, the AP biology students were nearing the end of the 17-day lab. At one table, junior Bridgett Meskis opened up her notebook where she was tracking data such as algae growth and was on the third day of tracking the brine shrimp, which they had added on day 10.

“We’re learning how different parts of the environment work together,” Meskis said.

The lab focuses on how abiotic (non-living) factors, such as temperature, light and salinity, for example, affect the population of algae and brine shrimp, Lillard explained.

“So we changed an abiotic factor to see how it affects the population of algae and then the brine shrimp eat the algae, so you know if we change the algae population it’s going to affect the brine shrimp as well,” Lillard said.

“They designed their independent variable — what they wanted to test — and so they had to have different hypotheses,” he added.

Meskis’ group changed salinity.

“We have all these samples of water and they all have different amounts of salt in relation to the water and then we put algae in,” Meskis said. “We let the algae grow and we measured how much of it there is and then put brine shrimp in. Will the ecosystem we’ve created favor algae or the brine shrimp?

“We’re trying to determine what the environment prefers, or what organisms prefer what environments,” she added.

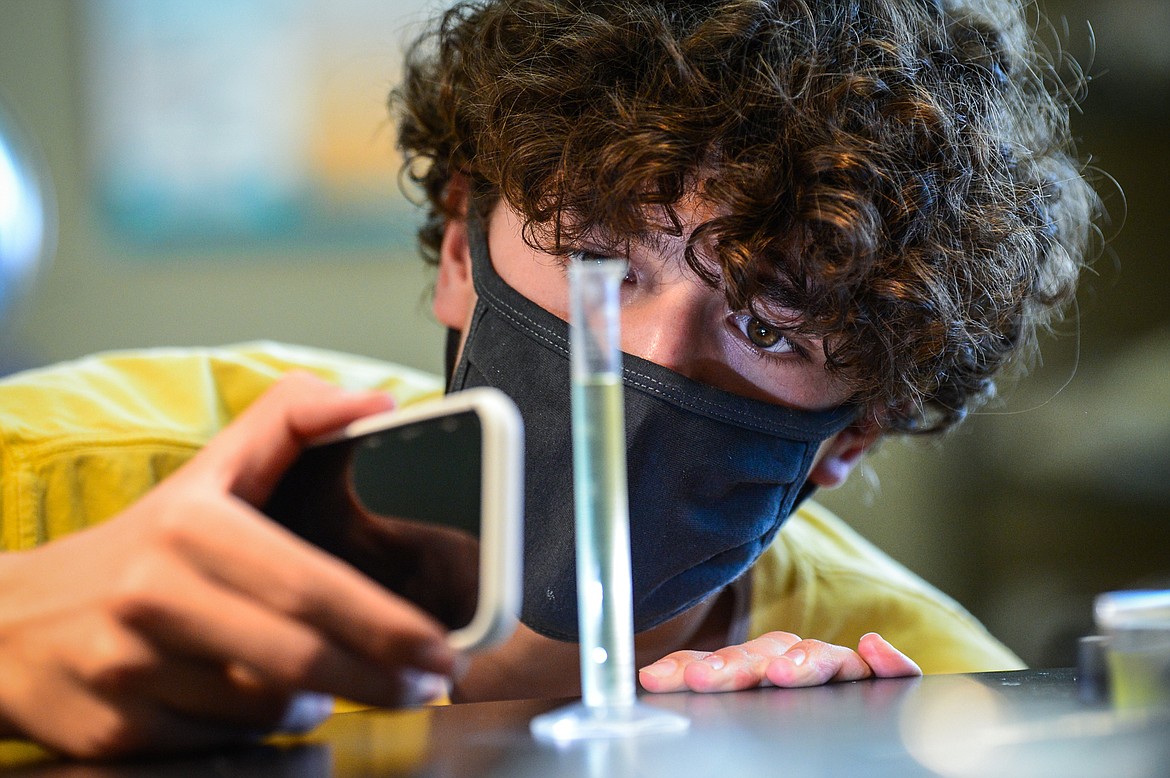

IN ANOTHER group, junior Marius DeVries said they changed light intensity using different bulb wattages. Group member Kait Giffin said the group hypothesized “If the populations have more light then they will grow better and faster.”

Counting the brine shrimp will tell how the algae population relates to the brine-shrimp population, DeVries said. In preparing to count the shrimp, DeVries turned on his phone’s flashlight function and held it up to a graduated cylinder containing the greenish liquid to better see the tiny aquatic crustaceans.

“The alga is a producer and it gets its energy and grows from the light and then the brine shrimp eat that,” DeVries said, basically showing how they limit each other.

He said at the end of the lab, the group plans to plot the data on a chart.

“Eventually, at the end, we can average the data and once we graph it we’ll be able to make a good conclusion.”

Lillard noted, “Hopefully they’re going to see how the population of algae has changed over that period of time.”

Reporter Hilary Matheson may be reached at 758-4431 or by email at [email protected]

ARTICLES BY HILARY MATHESON

Christmas tradition: Business continues helping customers capture the holiday spirit

Snowline Acres owners Tom and Kristin Davis are approaching a decade of helping people celebrate the most wonderful time of the year.

Whitefish High School wins East Helena speech and debate tournament

Scoring 225 points, the Whitefish High School speech and debate team took first place at a weekend tournament.

Glacier High speech and debate team secures second in Bozeman

The Glacier High School speech and debate team secured second place, and Flathead High School, third in Bozeman.