Night moves: Citizen scientists help document Glacier's pollinators

AVERY HOWE | Hagadone News Network | UPDATED 2 years, 4 months AGO

A waxing gibbous peeked above the treeline as nightfall darkened Glacier National Park on Saturday, July 29. Along Quarter Circle Bridge Road, mercury vapor lights stood like green torches as visitors from across the country, and nocturnal insects attracted to the glow, gathered around.

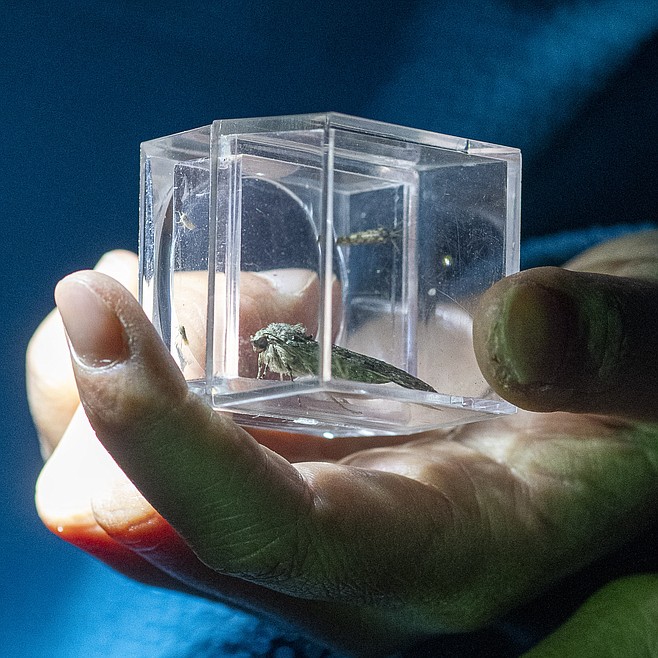

About 35 participants came to enjoy the Nocturnal Pollinator BioBlitz, a collaboration between Montana Moth Project and Glacier National Park Citizen Science Program, which allowed participants to capture and identify specimen with the help of experts. Stretched white sheets caught nocturnal insects dazed by the lights, and citizen scientists collected them in observation cubes to learn what they were and ultimately help document where they were.

“We don’t know anything about this world of pollinators, and we believe that they perform a pretty important role,” said Wildlife Biologist and Citizen Science Program Manager Jami Belt. At the time of the event, Glacier had roughly 35 to 40 moths in its museum collection. Montana Moth Project Biologist and Executive Director Mat Seidensticker anticipated that by the end of their latest collaboration with C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Research Associate Chuck Harp, they would record 350 to 400 species of moths found in Montana, four found for the first time ever in the state.

Belt went on to explain that moths are linked to plants - where fires have torn through, their larvae feed on new vegetation and contribute to nutrient cycling. Army cutworm moths are a known food source for grizzly bears within the park, as they make for an easy meal during their estivation period. Bats also benefit from the insects.

“They’re a great indicator species, because if you have a lot of moth diversity, it indicates you have a lot of vegetative diversity. They’re a great way to track environmental change and healthy ecosystems,” said Seidensticker.

The goal of the documentation is to serve as a baseline to document changes, whether species are staying or leaving, and how they are evolutionarily changing. “A collection over time gives a little snapshot of what is happening within an ecosystem, and this is a nice pristine area to be able to do that baseline study,” said Harp.

“You can’t preserve what you don’t know exists,” Belt added.

The scientists encouraged interested parties to participate through apps like iNaturalist and Leps, where citizen scientists can take photos on their cellphone to have specimen identified and geotagged. Harp noted that volunteers looking to help digitize records at Colorado State University’s museum are always welcome as well.

ARTICLES BY AVERY HOWE

Bug Creek project making headway near Bigfork

Flathead Area Mountain Bikers and Flathead National Forest will continue work on the forest’s first dedicated mountain bike trails around Crane Mountain this spring.

Neighbors, health department oppose addition to wellness retreat

Bigfork Land Use Advisory Committee heard a request from Samaa Retreat for a conditional use permit to add a retreat center building on their property on Aero Lane during their Thursday, Feb. 27 meeting.

Public offers mixed opinions on Lakeside sewer permit

Views were split in Thursday’s hearing. The majority of speakers were in favor of the permit, composed of public works employees, a few elected officials and members of the public.