Righting a wrong

JOEL MARTIN | Hagadone News Network | UPDATED 2 years, 5 months AGO

Joel Martin has been with the Columbia Basin Herald for more than 25 years in a variety of roles and is the most-tenured employee in the building. Martin is a married father of eight and enjoys spending time with his children and his wife, Christina. He is passionate about the paper’s mission of informing the people of the Columbia Basin because he knows it is important to record the history of the communities the publication serves. | September 15, 2023 1:30 AM

MOSES LAKE — It’s well known that racial disparities have historically existed in housing. Official racial discrimination – rules about which races can live where – hasn’t been legal in the U.S. for more than half a century, but its effects are still seen today.

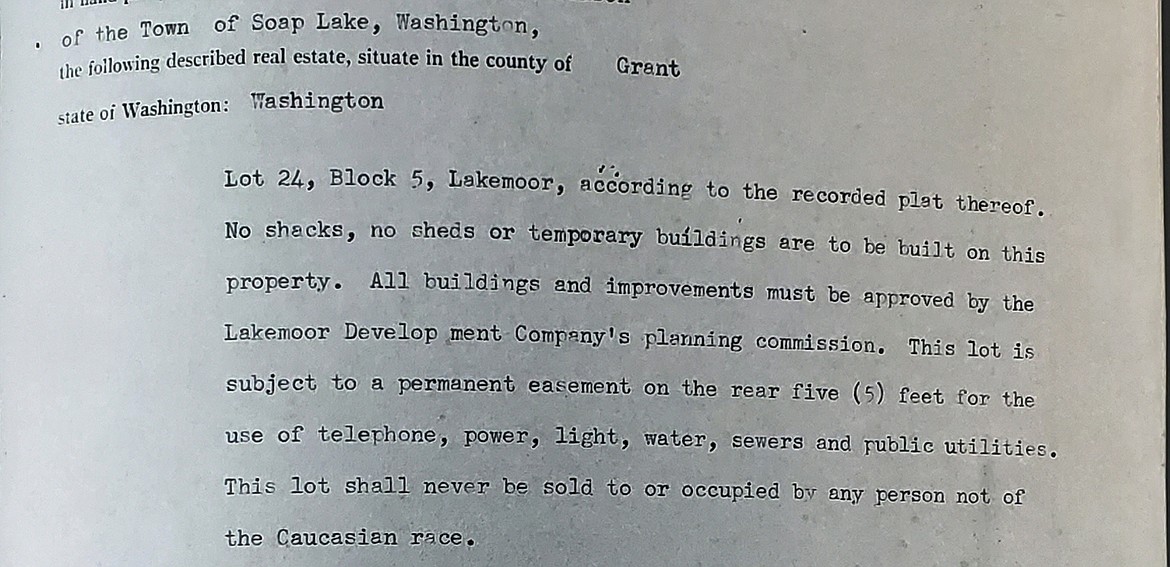

Until 1948, it was legal for a developer or homeowner who was selling property to include a stipulation, or covenant, in the deed prohibiting the sale or occupation of the property by anyone who wasn’t white. That year, the Supreme Court ruled that such covenants were unenforceable but because of the way property records are kept, they remain on the books even today. Racial discrimination of all kinds in housing was prohibited in 1968 by the Fair Housing Act, but unofficial discrimination still existed.

“Legal restrictions are not the only way that segregated housing was established and maintained,” Dr. Larry Cebula, a history professor at Eastern Washington University, told the Columbia Basin Herald in February. “There’d be much less formal things like a bank won’t give an African American a mortgage in a certain neighborhood. Or real estate agents won’t show a Hispanic family a house in a certain neighborhood. Neighbors might make a person of color feel uncomfortable through various levels of harassment. There’s a lot of ways this stuff happened.”

Cebula, a history professor at Eastern Washington University, was the manager of the Racial Covenants Project, which sought to identify racially restrictive covenants in land deeds in Washington. That process is now mostly completed, and one outcome of it could be a boon for first-time homebuyers who are members of racial minorities.

In Grant County, there were 89 covenants covering 164 homes, while in Adams County there was only one covenant applied to 62 lots. That’s 226 homes in the Basin that were off-limits to Black, Asian or other non-white buyers. Overall, the project identified more than 50,000 restrictive covenants.

In response to this discovery, the Washington Legislature, with bipartisan support, passed the Covenants Homeownership Account Act in May, aimed at correcting the effects of restrictive covenants, according to information published by the Washington State Housing Finance Commission. The act creates a special program for first-time home buyers who would have been excluded by a covenant – meaning ethnic minority members who resided in Washington before 1968 – that helps cover down payments and closing costs, expenses that make first-time home buying a challenge.

There aren’t a whole lot of first-time home buyers these days who were around before 1968, so at first glance, the program seems like just a nice but hollow gesture. However, the program also applies to any descendant of such a person, provided they are themselves Washington residents and have an annual income at or below the area median income. In Grant County, that’s $76,500, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. In Adams County, it’s $65,500. Extending that assistance to descendants of people who would have been discriminated against means a much wider field of beneficiaries.

Exactly who that would be is a little uncertain. The text of the law refers to “black, indigenous, and people of color and other historically marginalized communities.” Racial covenants frequently specified that Blacks or Asians were prohibited from purchasing or occupying restricted residences. Whether it also applies to Hispanic people, who were not specifically named in racial covenants but might have been discriminated against, is not specified. At the same time, Jewish people were sometimes specifically named, and in a few cases Catholics were as well. Neither the Northwest Fair Housing Alliance, which is researching the matter for eastern Washington, nor its west side counterpart the Fair Housing Center of Washington, returned phone calls asking for clarification.

Right now, research is as far as the project has gone. The National Fair Housing Alliance, partnered with the NFHA and the FHCW, is conducting the Covenant Homeownership Program Study, according to the WSHFC.

“This evidence-based research study will investigate housing discrimination against marginalized communities in Washington state, what role government institutions have had in the discrimination, the impacts of the discrimination and what specific assistance would be likely to remedy these impacts,” according to information from the WSHFC.

In January, the state will begin collecting funds to finance both the study and the assistance program, according to the WSHFC’s timeline. The money will come from a special fee of $100 collected by county auditors for every real estate document recorded, which will begin to be assessed in January.

“For many years, Washington state mandated that county auditors record racially restrictive real-estate covenants,” the WSHFC wrote. “Legislators found it fitting that this same document-recording process should help remedy the harm created by these actions.”

Joel Martin may be reached via email at [email protected].

ARTICLES BY JOEL MARTIN

Space Burger booth open March 13-15

MOSES LAKE — Those who can’t wait for the Grant County Fair can get their Space Burger fix next weekend, according to an announcement from the Lioness Club of Moses Lake. The iconic Grant County sandwiches will be available at the Grant County Fairgrounds March 13-15, according to the announcement. There is no admission fee to get into the fairgrounds that weekend.

SENIOR EVENTS: March 2026

COLUMBIA BASIN — Plays, art shows, auctions and more await seniors in the Columbia Basin this month. Here are some opportunities to get out and about in March.

Valentine’s Day cards flood Brookdale Hearthstone with love

MOSES LAKE — Residents at Brookdale Hearthstone Assisted Living in Moses Lake got Valentine’s Day greetings from across the country last month. “I believe that the only states we have not received (cards from) yet are Vermont and Maine,” Lifestyle Director Imelda Broyles said Feb. 24. “We keep receiving new cards every single day. They have not stopped. My residents are in awe with every single one of the cards that we’ve been receiving.” The Hearts Across America project started as a way for children in school classrooms to exchange Valentine’s Day cards with classes in other states or even countries, but the idea has expanded to senior living facilities, according to the project’s social media.