Montana mining history — Kalispell eighth-graders pan for gold and garnets

HILARY MATHESON | Hagadone News Network | UPDATED 1 year, 11 months AGO

A sign above Montana History teacher Kris Schreiner's classroom alerts Kalispell Middle School eighth graders that they are entering Alder Gulch to mine for gold and garnets.

Alder Gulch, was the site of the “richest placer gold strike in the Rocky Mountains with an estimated total value of 100 million dollars throughout the 18th and 19th century,” according to virginiacitymt.com. A man by the name of William Fairweather discovered the site in May 1863.

“Fairweather dug the dirt, filled a pan and told Edgar to wash the pan in the hope of getting enough gold to buy tobacco. When the first pan turned up $2.40, they knew the gulch had great potential.”

Miners flooded in as word spread. The population surge led to the establishment of Virginia City and Nevada City, locations the students learned about as part of a mining unit in addition to Alder Gulch. Other notable sites Schreiner had marked on a map of Montana were Bannack, Fort Ellis (Bozeman), Butte City, Lost Chance Gulch (Helena), Hell Gate (Missoula), Fort Shaw, Sun River, Fort Benton and Fort Carroll.

“We covered the mining era of Montana all the way to the present day,” Schreiner said, from traditional placer mining to hardrock and open pit mining methods that are used today.

On this day in the classroom, large batches of the alluvial gravel Schreiner collected from a friend’s ranch over the summer are washed in two sluices with battery-operated pump circulation systems, mimicking the flow of a stream. The sluices were purchased through Kalispell Education Foundation grants.

“We’ve done the gold panning before but we haven’t had a pump circulation sluice system. We’ve had some sluices, but kids had to pour buckets of water and you don’t get the right action,” Schreiner said. “Basically, it concentrates all the heavy material in our mine dirt, so they’re not having to do as much cleaning in the gold pan.”

The students were doing what is called placer mining, which involves separating minerals like gold from sand, gravel and clay in streambeds.

“Most miners in the late 1800s built their own sluices along creeks just out of wooden flume,” he said.

“Essentially all they would do is just set it up along the river and they would shovel their dirt in and it would wash all the material they didn’t want at the end. And that’s a lot of the environmental impact in any area that was placer mined because they washed so much of the river systems. They would build their own and then they would abandon them as gold ran out.” This would remove nutrient-rich topsoil.

“If you go to major placer areas like down by Virginia, Nevada City, you can still see the remnants of all that environmental degradation that took place from the topsoil of people placer mining and even hydraulic mining the river systems,” Schreiner said.

STUDENTS LINED up at a desk designated at the “assayers office” to collect the pay dirt they earned by completing assignments. The more work they finished the more dirt they received.

Gathering in groups around water-filled totes, students dropped dirt and water in pans, which they moved in a circular motion.

“So keep that swirling motion and you're going to keep washing away the top layers until you get down to the heavy stuff in the corner, which should be garnets and gold,” Schreiner said while demonstrating. “You can just kind of tap on the side and that’s gonna bring up those lighter rocks.”

He said the process stratifies the material.

“Stratifying just means allowing it to separate into layers — letting the heavier material go to the bottom and the lighter material go to the top, so quartz and a number of other rocks that we have in this mix,” he said.

“You want to wash that off the top and allow anything like gold and garnets, heavier-density materials to work to the bottom. Then, we wash our pan. We go water in, water out,” he said dipping the pan in the tote of water. “So we reduced the top layer, but we don’t want to [let] go too much. We want to stratify again.”

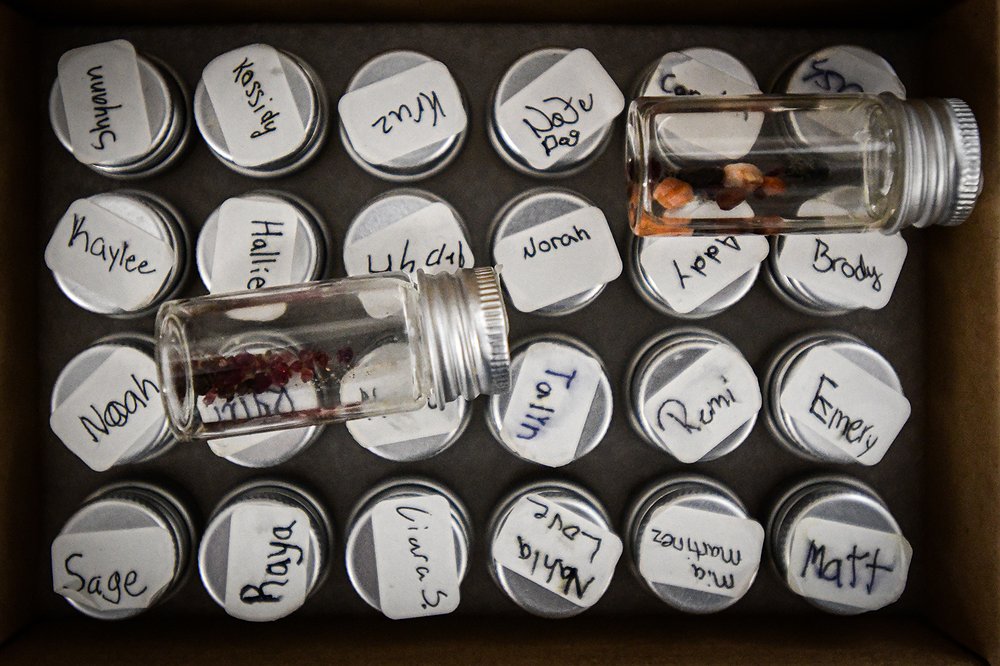

While the students knew they weren’t going to strike it rich, they carefully sorted through the dirt with tweezers, smiling with satisfaction after spotting a glinting flake of gold or the reddish hue of garnet, which they plucked out.

“It’s a lot of patience. A lot of patience,” eighth-grader Elliana Morris said.

“Then, you end up with some of this,” classmate Gage Sneeden said, picking up a capped vial containing a layer of tiny garnets.

“She found the biggest garnet,” Sneeden said, pointing over to classmate Lucy Holloway.

Holloway wasn’t certain if that was a fact, but showed the garnet, which was not bigger than a pencil eraser. While sifting through the dirt for garnets the students look at color.

“Garnets, they're more pink and red, darker reds,” Holloway said, turning her vial to show the variety in the color.

“They’re more clear,” she said, in comparison to rocks that might appear reddish.

When it comes to looking for gold, eighth-grader Izaac Coronado said the key is to look for shine. Sifting through the dirt with tweezers, he points out a sparkle speck in the dark brown dirt. He pondered if it was gold or pyrite, also known as fool’s gold.

“Is that gold, that little speck up there?” Coronado asked Schreiner.

“Yep, you got a flake right there,” Schreiner said.

Coronado said he had a larger piece of gold in his vial that was easier to spot.

“It’s hiding under all these garnets,” he said, lightly shaking the vial. “Right there above my finger, it’s dull because it’s a thicker lump.”

Earlier, Sneeden explained one way of telling if a mineral is pyrite or gold.

“Pyrite, if you find a chip of it, it’s easy to snap,” Sneeden said.

There was also the potential to find gold-laced quartz, which Sneeden said he found before during a gold mining trip years ago with his dad at Libby Creek.

“Most of it was in the quartz rocks out of the ground. We’d find big huge chunks of quartz with gold,” Sneeden said.

A projection showing an example of quartz containing gold was displayed on the wall along with other minerals students might find such as rhodonite.

At the end of the class period, students pack the vials neatly in a box. At the end of the project, they will get to keep a piece of Montana’s geologic history.

Observing the hands-on project was Kalispell Education Foundation Director Dorothy Drury.

“I just heard a kid saying this is so much better than school, but this school,” Drury said, smiling.

Foundation grants have allowed Schreiner to purchase supplies for other engaging hands-on projects including hide tanning, butter churning and building a log cabin. Whereas before he would purchase supplies using his own money. It’s not uncommon for teachers to do when there aren’t available funds in the budget, according to Drury. She said these are the favorite teachers adults remember making school special.

“These are all our teacher’s ideas who know what their students need,” she said. “It's such a privilege to be able to support the ideas that he knows are going to better connect kids to their learning.”

For more information about the foundation, or to donate, visit www.kalispell education foundation.org.

Reporter Hilary Matheson may be reached at 758-4431 or [email protected].

Kalispell Middle School teacher Kris Schreiner demonstrates how to use a sluice to eighth-graders, from left, Shyann Richsel, Kaylee Whitten and Hallie Granley during a lesson on panning for gold, garnets and other minerals in his history class on Tuesday, Jan. 16. (Casey Kreider/Daily Inter Lake)

Kalispell Middle School teacher Kris Schreiner demonstrates how to use a sluice to eighth-graders, from left, Shyann Richsel, Kaylee Whitten and Hallie Granley during a lesson on panning for gold, garnets and other minerals in his history class on Tuesday, Jan. 16. (Casey Kreider/Daily Inter Lake)Casey Kreider

ARTICLES BY HILARY MATHESON

Christmas tradition: Business continues helping customers capture the holiday spirit

Snowline Acres owners Tom and Kristin Davis are approaching a decade of helping people celebrate the most wonderful time of the year.

Whitefish High School wins East Helena speech and debate tournament

Scoring 225 points, the Whitefish High School speech and debate team took first place at a weekend tournament.

Glacier High speech and debate team secures second in Bozeman

The Glacier High School speech and debate team secured second place, and Flathead High School, third in Bozeman.