Over the Hill: Exploring North Idaho's very own ghost town

HAILEY HILL | Hagadone News Network | UPDATED 1 year, 5 months AGO

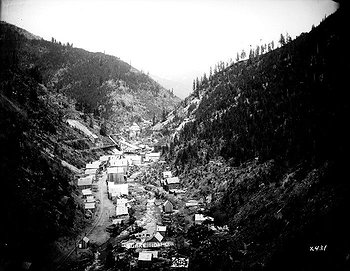

BURKE — If you head east out of Wallace on State Highway 4, civilization seems to fall away quickly — the forest is even thicker, the canyon walls rise higher and the space between them grows narrower. It is difficult to tell whether the few houses you pass are inhabited. And you can forget about getting a signal on your cellphone.

Undoubtedly, such a drive is not everyone’s idea of a good time. But for fans of adventure — especially the odd and unsettling — continue about 7 miles on this narrow, deteriorating backroad and you’ll find yourself in the ghost town of Burke.

Idaho reportedly has about 100 “ghost towns” throughout the state — while some are maintained as tourist attractions, Burke can truly be deemed “abandoned.”

While most of the town’s buildings have fallen victim to fire and avalanche, massive structures from Burke’s once-thriving mining operations remain standing against the test of time. A few small, dilapidated wooden houses still cling to the steep canyon walls, and the few commercial buildings left along the road offer proof of “what once was” in a place that now appears void of almost all human activity.

Standing among these buildings, the silence looms as large as the canyon itself. I couldn’t shake the feeling that I was being watched — a feeling that has been reported by other visitors to the area, and rumors of paranormal activity have circulated for years. After diving into the town’s tumultuous history, thinking back on that feeling only becomes more eerie.

Burke grew quickly as a mining town following the discovery of silver and lead deposits in the canyon — people were also drawn to the area because of its unique architectural design, born out of necessity due to the extremely narrow geography of the canyon.

The famous Tiger Hotel, which has unfortunately been torn down, was designed to allow the railroad (which also shared the town's main road) to pass through its lobby. Many homes were built into cave-like holes in the steep canyon walls.

However, Burke seemed to fall as quickly as it grew. Labor disputes between miners and mine owners often grew violent — in 1892, riots had to be quelled by the National Guard and martial law was declared.

The canyon also saw more than its fair share of natural disasters, including deadly avalanches and immensely destructive fires. The United Press reported July 14, 1923, that 600 people in Burke were made homeless by a massive fire, which destroyed most homes and over 50 commercial buildings.

Following these repeated disasters, the mines began shutting down. The last mine closed in 1991, and today only a few people (at the most) call the canyon home.

Despite Burke being well off the beaten path, fencing, barbed wire and “no trespassing” signs block the especially adventurous from entering the deteriorating buildings — but for obvious safety reasons, this is probably for the best. There also appears to be roadwork activity in the area, though none of the equipment was in use when I made the trip out.

Even noting these small reminders of modern civilization, visiting Burke is a genuinely eerie experience. The dramatic scenery — and the unshakable feeling that someone (or something) was watching you — sticks with you long after you leave the canyon.

ARTICLES BY HAILEY HILL

Trouette appealing town hall verdict

Seeks return of security company license

Security company owner Paul Trouette is appealing the revocation of his security agency and security agent licenses following his December conviction on two counts of battery and violations related to security agent uniform and duty requirements, all misdemeanors.

Idaho's first Crunch Fitness to open in Coeur d'Alene

Crunch Fitness is coming to Coeur d'Alene.

Valentine's preparations underway in Coeur d'Alene

With Valentine’s Day less than 48 hours away, Hansen’s Florist and Gifts was bursting with chocolates, stuffed animals, balloons, and flowers. Lots and lots of flowers.